Keeping Patients and Staff Safe During Perioperative Spinal Surgery Prone Positioning

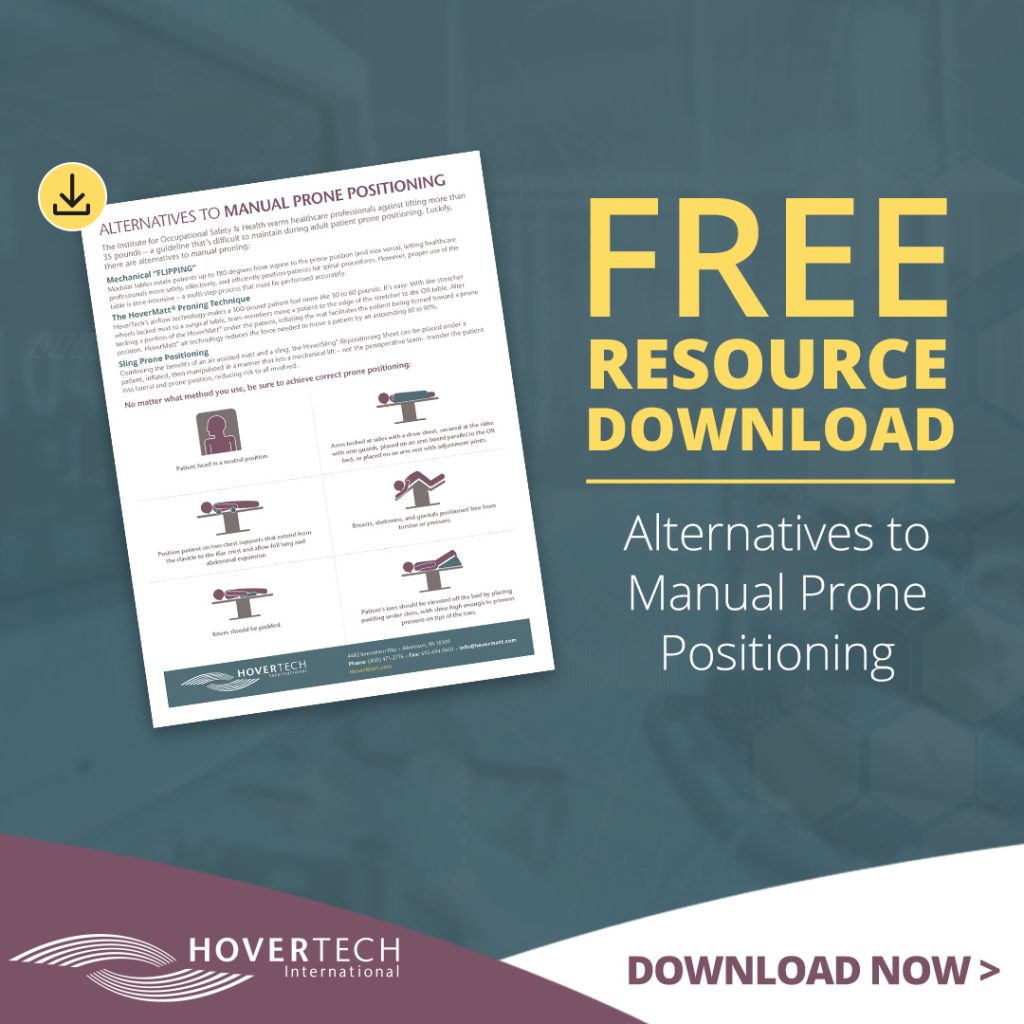

Download the FREE resource guide

Download the FREE resource guide: Alternatives to Manual Prone Positioning PDF

Listen to HoverTech’s webinar on Safe Patient Handling During Spinal Surgery and earn one contact hour!

Spinal procedures are among the most commonly performed medical procedures worldwide, exacerbating a well-documented problem: The elevated risk of musculoskeletal injuries among nursing staff during perioperative prone positioning.

Positioning a patient prone (essential for operative access to the dorsal aspects of the body) holds risk for patients, too. Most are under complete or partial anesthesia during transfer to the ventral (face-down) prone position. This decreases the opportunity for patient communication and requires the perioperative nurse to be a strong patient advocate while positioning. Furthermore, prone positioning has a razor-thin margin for error. When executed incorrectly, patient risk factors climb.

Here, we’ll discuss ways to protect staff and patients alike during prone positioning.

Nursing Risk Factors During Prone Positioning

Protecting nurses is vital in any scenario, but gains urgency when you look at the numbers: Patient handling-induced claims are the highest of all workers’ compensations claims, averaging $14,000. Worse yet, injuries incurred at work can have ongoing and sometimes extreme impacts on nurses’ careers and lives.

The prevalence of occupational injuries – and musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) in particular – among operating room nursing staff is higher than in nonspecialized nursing. Astoundingly, an estimated 90% of nurses will report musculoskeletal injuries in their careers. Defined as dysfunctions that can affect muscles, bones, joints, or spinal discs, common musculoskeletal disorders include tension neck syndrome, tendonitis, rotator cuff tendonitis, fibromyalgia, and osteoarthritis (OA).

MSDs typically result from prolonged exposure to activities that are frequent and repetitive – like these four movements essential to manually transitioning a patient into prone (which generally involves rotating patients into a lateral side-lying position, then carefully log rolling them downward onto the abdomen and into prone):

- Lumbar spine in position of extension

- Generating force with the lumbar spine in extended position

- Rapid movement of the spine from position of extension to position of flexion

- Supporting patient body weight while in a position of lumbar spine extension

Patient Risk Factors During Prone Positioning

Risks associated with prone positioning extend to patients. Shearing can occur when skin moves against a fixed surface. Incorrect prone positioning can lead to orbital pressure resulting in postoperative vision loss (a potentially permanent condition). Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve neuropathy in 20% of spinal surgery cases causes pain and dysesthesia in the anterolateral thigh. Inappropriate pressure on vital structures of the abdomen can cause ischemia and organ failure.

Protecting Nurses and Patients During Prone Positioning

Making prone safer for nurses and patients alike starts with understanding the position itself:

- A patient in prone must be appropriately aligned, with the head in a neutral position.

- Options for patient arm placement: Tucked at the sides with a draw sheet, secured at the sides with arm guards, placed on an arm board parallel to the OR bed, or placed on an arm rest with adjustment joints designed for this purpose.

- Position patient on two chest supports that extend from the clavicle to the iliac crest and allow full lung and abdominal expansion.

- Breasts, abdomen, and genitals should be positioned so they are free from torsion or pressure.

- Knees should be padded.

- Patient’s toes should be elevated off the bed by placing padding under shins, with shins high enough to prevent pressure on tips of the toes.

The complexities of these parameters introduce the million-dollar question: How do nurses accomplish all of the above without exacerbating the risk of an MSD?

Consider these alternatives to manual prone positioning.

Mechanical “Flipping”

The Jackson Table is used by many healthcare facilities to safely, effectively, and efficiently position patients for spinal procedures.

The table has the unmatched ability to rotate patients up to 180 degrees from supine to the prone position (and vice versa). While the Modular Table System frees staff from the rigors of manual prone positioning, proper use of the device is time-intensive – a multi-step process that must be performed accurately. Like all solutions, it comes with risks. Fixing the chest and iliac crest gel pads underneath a patient resting in prone position, for example, can lead to complications including hyperextension of the cervical and lumbar spine.

The HoverMatt® Proning Technique

The Institute for Occupational Safety and Health recommends lifting no more than 35 pounds – a parameter that’s often impossible to maintain during adult patient prone positioning. The good news: Operating within these boundaries becomes possible with the HoverMatt proning technique:

A stretcher with wheels locked is positioned next to a surgical table; team members position the patient at the stretchers edge. Next, approximately 4” of the HoverMatt is tucked under the patient’s body closet to the OR Table while securing that arm with a pillowcase. With four (4) caregivers (minimum) in place, the HoverMatt SPU is inflated to turn the patient toward a prone position. HoverTech’s airflow technology makes a 300-pound patient feel more like 30 to 60 pounds, an astounding 80-90% force reduction.

Sling Prone Positioning

Another resource for safer prone positioning is the HoverSling® Repositioning Sheet. Combining the benefits of an air-assisted mat and a sling, HoverSling can be placed under a patient, inflated, then manipulated in a manner that lets a mechanical lift – not the perioperative team– transfer the patient into lateral and prone position, reducing risk to all involved.

The LiFFT Risk Assessment Tool

Shorthand for Lifting Fatigue Failure Tool1, the LiFFT risk assessment tool is a method of evaluating lower back risk associated with manual lifting. LiFFT is based on fatigue failure theory, which assesses the cumulative damage of materials to repeated stress.

LiFFT’s purpose is to determine the cumulative low back load experienced during a workday. Based on its measure, the probability of the job’s risk is calculated. A high-risk job is defined as a job having 12+ injuries per 200,000 hours worked.

Use of LiFFT requires three pieces of information on each lifting task:

1. Weight of the load

2. A measurement of the greatest horizontal distance from the hip joint to the center of the load during the lift (use a measuring tape)

3. The number of repetitions of this task during the workday

Head to LiFFT’s website to learn more about LiFFT in operating room decision-making.

Establish a Safe Patient Handling and Mobility (SPHM) Program

Healthcare employers and employees should work together to establish a formal, systematized Safe Patient Handling and Mobility (SPHM) program designed to reduce the risk of injuries including MSDs. It starts by performing a needs assessment, then developing a plan, implementing said plan, and evaluating it on a monthly basis. Click here to learn more about developing a SPHM in your workplace.

Want to learn more about alternatives to manual prone positioning? Download the Alternatives to Manual Prone Positioning Resource Guide.

For more resources and education about safe patient handling, reach out to HoverTech.

[1] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0003687017301023